How Closing Big Tech Tax Loopholes Became Trump’s Quiet Path to Tackling the National Debt

Can Big Tech’s Billions Plug Trump's Fiscal Firestorm?

As U.S. Debt Soars Past $36 Trillion, Eyes Turn to a New Goldmine: Tax Revenue Left on the Table

The U.S. national debt is burning a hole through every political promise. At $36.56 trillion and climbing, it now towers over the nation’s economy, a staggering 123% of GDP.

U.S. National Debt as a Percentage of GDP Over Time

| Year | Debt-to-GDP Ratio (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 124.7 - 126.3 | All-time high recorded by some sources, pandemic spending |

| 2021 | 118.9 | Decreased from 2020 peak |

| 2022 | 110.4 | Continued decrease from 2021 |

| 2023 | 122.3 | Increased again |

| 2024 | 98.0 - 124.0 | Estimates vary (98% fiscal year-end, 124% Dec) |

| 2025 | 123.0 (Projected) | Treasury Fiscal Data projection for FY |

| 2034 | 116.0 (Projected) | CBO projection |

| 2035 | 118.0 - 118.5 (Projected) | CBO/Visual Capitalist projections |

Meanwhile, as Washington hunts for answers, some analysts say the most obvious pile of cash remains stashed offshore — not in vaults, but in digital assets, paper structures, and legal loopholes expertly maneuvered by the titans of American technology.

In a stark fiscal moment defined by swelling deficits and mounting interest costs, a provocative new question is gaining traction in D.C. and Wall Street alike: Could clawing back taxes long avoided by Big Tech provide the lifeline President Trump needs to stabilize America’s finances — or at least claim he is?

The Collapse of the “Dutch Sandwich” Era — and What Replaced It

For decades, U.S. tech giants operated behind a latticework of legal tax shelters, most famously the “Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich,” which allowed companies to route global profits through Ireland and the Netherlands to no-tax havens. That strategy effectively died by 2020, strangled by Irish reforms and multinational pressure.

The "Double Irish with a Dutch Sandwich" was a prominent international corporate tax avoidance strategy. It involved routing profits through Irish and Dutch subsidiaries to exploit loopholes and significantly lower tax liabilities on non-US earnings, though legislative changes have largely closed this structure down.

But those billions in vanishing taxes didn’t come home — they merely changed addresses.

Today, multinationals wield a new toolkit of refined tactics. Among the most potent: Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets (CAIA) in Ireland, income aggregation under GILTI and FDII rules, earnings stripping, tax inversions, and a rising tide of multi-layered partnerships.

The New Architecture of Avoidance: How Big Tech Rewired the Global Tax Map

Today’s avoidance schemes are no longer routed through obvious havens. Instead, they are nested in legal abstractions, synthetic pricing structures, and internal corporate transactions that defy the spirit of tax law while staying just inside its letter.

What follows is not evasion. It is design.

Repatriating the Intangible: How IP Became an Accounting Weapon

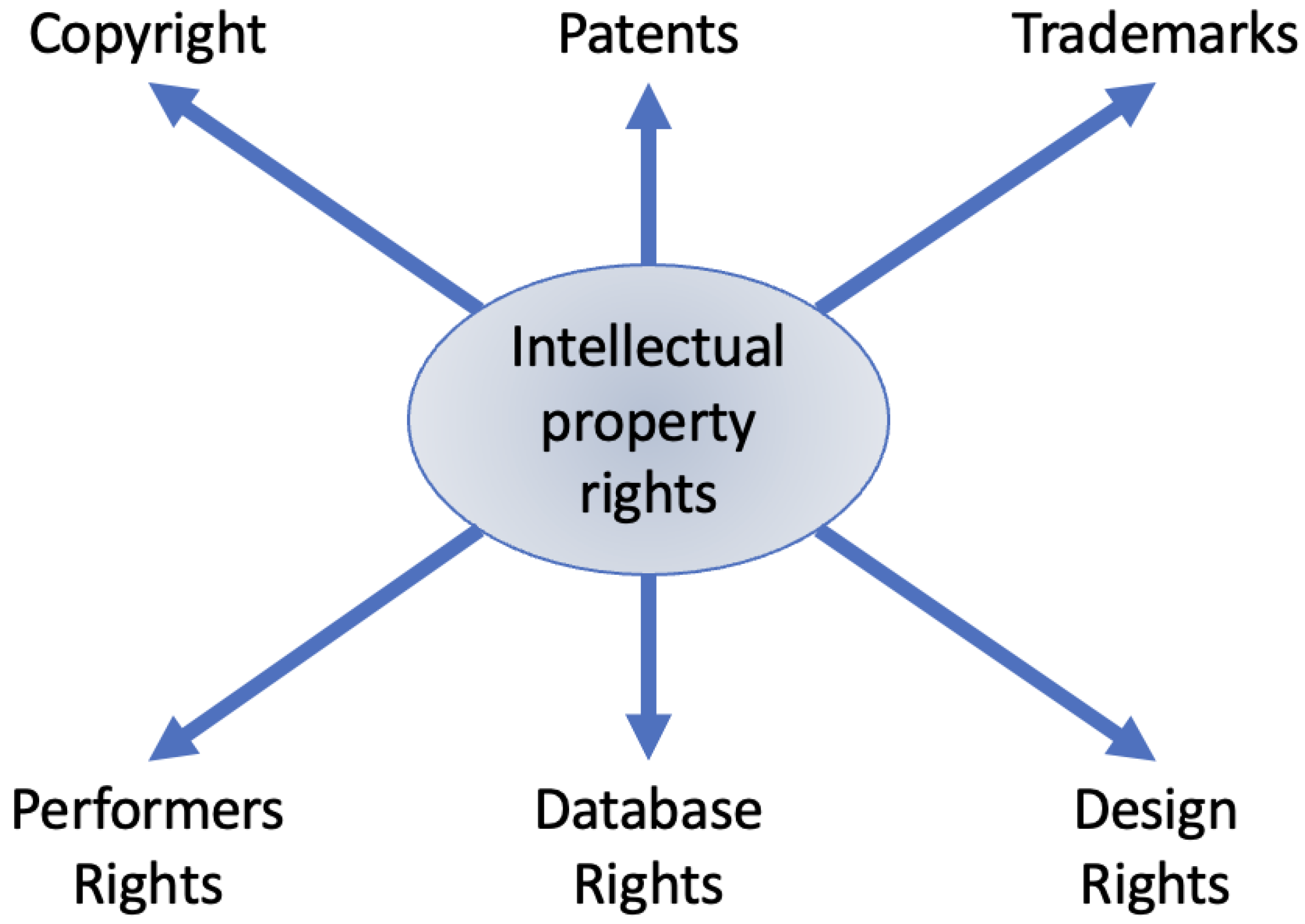

One of the most consequential transformations has been the aggressive monetization of intangible assets — patents, algorithms, source code — and their deployment as tax shields through capital allowances.

Under Ireland’s Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets (CAIA) regime, companies can deduct the full cost of acquired intellectual property from their taxable income. Many of these acquisitions, however, are made internally: a subsidiary in Ireland buys global IP rights from another arm of the same corporation. The transaction is priced at tens of billions of dollars — then depreciated over time to systematically erase profits.

Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets (CAIA) provide tax relief for companies on the costs of acquiring specified intangible assets, such as intellectual property. This essentially allows businesses to write off or amortize these costs against their taxable profits over a set period, subject to specific rules like those applicable under Irish tax law.

In one illustrative case, a major U.S. technology firm reassigned core software patents to its Irish affiliate in 2015 at a notional price exceeding $100 billion. For the next decade, that subsidiary will report nearly no taxable income in Ireland — despite handling a large portion of the firm’s global revenue.

The Blurred Borders of GILTI and FDII

The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act introduced new provisions — notably, Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) and Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII) — aimed at curbing offshore profit shifting. But companies quickly found a workaround: averaging.

Table summarizing the key features of GILTI and FDII provisions in U.S. tax law, introduced under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

| Feature | GILTI (Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income) | FDII (Foreign-Derived Intangible Income) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Foreign earnings via Controlled Foreign Corporations (CFCs) | Foreign-source income earned directly by U.S. corporations |

| Purpose | Tax foreign intangible income to discourage profit shifting abroad | Incentivize export-related intangible income to encourage domestic investment |

| Target | Intangible income held abroad | Intangible income derived from exports |

| Effective Tax Rate | 10.5% (13.125% post-2025) | 13.125% (16.4% post-2025) |

| Deduction | 50% deduction under Section 250 | 37.5% deduction under Section 250 |

| Deemed Return on Tangible Assets | Exemption for 10% of Qualified Business Asset Investment (QBAI) | Exemption for 10% of QBAI |

By blending income from high-tax and low-tax jurisdictions, multinational corporations reduce their apparent foreign tax rate and avoid triggering GILTI penalties. A dollar in Bermuda (zero percent) offsets a dollar in Germany (30 percent), and the effective rate appears benign. The tax code sees balance; the balance sheet sees arbitrage.

A corporate tax advisor familiar with this practice noted, “The law assumes each jurisdiction is a silo. But in a globalized structure, they’re just pipes in a system designed to equalize — and minimize — exposure.”

Internal Debt and the Cost of Capital Manipulation

Another common tactic: the strategic deployment of intra-company debt. U.S. subsidiaries borrow from their own foreign affiliates and pay interest on that debt, which becomes deductible domestically but lightly taxed abroad — or deferred entirely.

This method, known as earnings stripping, has long been contested by regulators. But under specific thresholds, it remains legal. One analyst described it as “a company paying itself to create a tax loss.”

Table: Overview of Earnings Stripping - Definition, Mechanism, and Regulations

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Definition | A tax avoidance strategy where corporations reduce domestic tax liabilities through excessive interest deductions. |

| Mechanism | Parent companies in low-tax jurisdictions lend money to subsidiaries in high-tax jurisdictions, allowing subsidiaries to deduct inflated interest payments from taxable income. |

| Profit Shifting | Income is shifted to the parent company in a low-tax country, minimizing overall corporate taxes. |

| Legal Framework | Governed by regulations like U.S. IRC Section 163(j), which caps interest deductions at 30% of adjusted taxable income. |

| Global Efforts | Initiatives like BEPS aim to curb excessive profit shifting and earnings stripping practices. |

| Impacts | Reduces government tax revenues but provides significant savings for corporations. |

| Prevention Measures | Fixed ratios for deductible interest (e.g., EBITDA-based limits) ensure some profits remain taxable in high-tax jurisdictions. |

Invisible Networks: Partnerships, Pass-Throughs, and the Rise of Shadow Structures

Perhaps the most opaque domain of modern tax planning lies in the rise of complex partnership networks and “blocker corporations” — structures designed to allocate profits, losses, and liabilities across layers of entities in multiple jurisdictions.

In one case under IRS scrutiny, a single technology firm filed over 130 separate tax returns to account for a web of partnerships, many of which routed profits through Delaware, Luxembourg, and the Cayman Islands. The resulting U.S. taxable income? Nearly zero.

Even experienced auditors struggle to disentangle these structures. As one Treasury official, speaking under condition of anonymity, put it: “We know there’s gold in there. But first we’d have to map the mine.”

Transfer Pricing 2.0: The Market of One

Transfer pricing — the practice of pricing transactions between subsidiaries — has become more nuanced. Under current law, internal licensing agreements and service charges must be set at “arm’s length,” as though they occurred between independent firms. But when a company licenses its own IP, there is no market — and the price is effectively whatever it says it is.

Transfer pricing refers to the pricing of internal transactions between related entities within a corporation. This practice is heavily scrutinized for taxation purposes, requiring adherence to the arm's length principle, which dictates that prices should be set as if the entities were unrelated and operating in a competitive market.

For example, a platform’s U.S. operations might pay its European arm billions annually for “technology services,” pushing taxable income offshore. Regulators face a conundrum: a transaction is documented, internally consistent, and formally disclosed — but economically engineered to hollow out the U.S. tax base.

The Numbers Behind the Vanishing Revenue

From 2018 to 2023, Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon alone extracted over $26 billion (which is already an underestimation by many experts) in federal tax benefits through mechanisms like foreign-derived intangible deductions and IP cost recovery.

Zoom out, and it’s clearer still: across 15 major corporations, over $50 billion in tax breaks flowed through the system in five years. If trends held into 2024 and 2025 — and early data suggests they did — that figure may now exceed $60 billion per year in legal but aggressive tax avoidance by large multinationals.

Statutory vs. Average Effective Corporate Tax Rates for Large U.S. Companies

| Description | Statutory Rate (Federal) | Average Effective Rate | Year(s)/Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) | 21% | N/A | Since Jan 1, 2018 |

| Average Rate for Large Profitable Corps (GAO Study) | 21% | 9% | 2018 (down from 16% in 2014) |

| Average Rate for 342 Largest Consistently Profitable Corps (ITEP Study) | 21% | 14.1% | 2018-2022 |

| Average Rate for 296 Largest Consistently Profitable Corps (ITEP Study) | 21% | 12.8% | 2018-2021 (down from 22.0% in 2013-2016) |

| Example of Low Rates (ATF Study on GE, GM, Meta, Tesla, T-Mobile) | 21% | 6.9% | 2023 |

| Combined Federal and State Statutory Rate | ~26% | N/A | As of 2023 |

An expert familiar with these structures remarked, “These aren’t illegal. But they’re absolutely engineered. And they’re engineered to drive the effective tax rate toward zero — especially for profits that touch no U.S. soil.”

A recent study examining 342 profitable U.S. companies found:

- The average effective tax rate: 14.1% — far below the statutory 21%.

- Nearly 25% of these companies paid single-digit effective rates.

- 23 companies paid zero federal income tax over five consecutive years.

In response, the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act introduced a 15% corporate alternative minimum tax aimed at about 100 major companies. But enforcement remains narrow, and corporate tax engineers have already shifted toward structures that evade this net — often through cross-border profit-blending or exotic partnerships that outpace IRS oversight.

Did you know that the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CAMT), introduced by the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, ensures large corporations pay at least a 15% tax on their financial statement income? This tax applies to corporations with over $1 billion in average annual income (or $100 million for U.S. subsidiaries of foreign companies) and aims to prevent them from drastically reducing their tax liabilities through deductions and credits. Effective from 2023, CAMT represents a major shift in corporate taxation, requiring companies to calculate taxes under both regular rules and the CAMT, paying whichever is higher!

Can Trump Really Use This to Kill the Debt Beast?

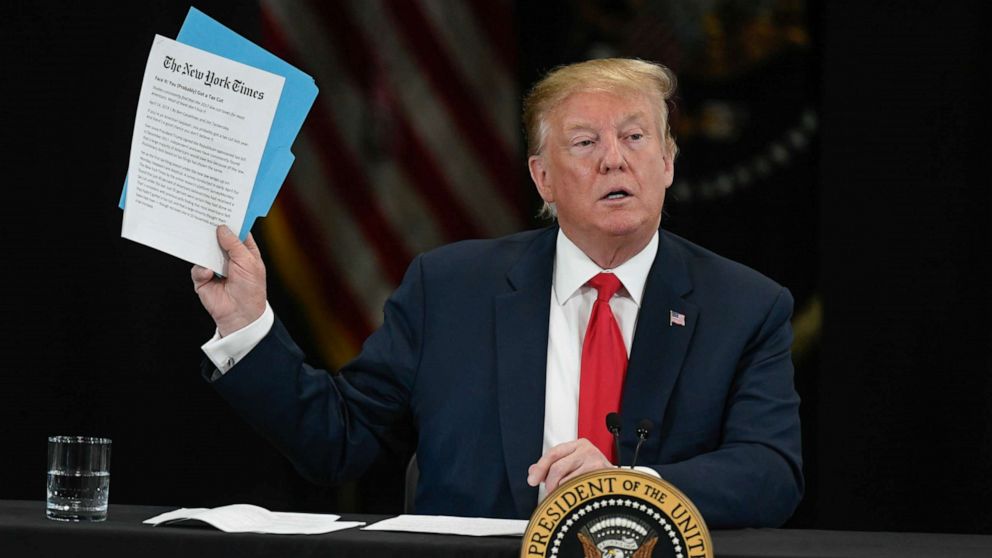

As of February 2025, President Donald Trump reentered the fiscal ring with ambitious — and conflicting — promises: cut the national debt by $1 trillion, make the 2017 tax cuts permanent, and finance tariffs without tanking growth. Yet, analysts warn the math doesn’t add up.

Those 2017 cuts are projected to add $7.75 trillion to the debt by 2035. Tariffs have spiked volatility and borrowing costs. Meanwhile, annual interest payments on the debt are now breaching $1 trillion — more than the defense budget.

But if the political optics are shaky, the political theater is not. According to senior campaign advisors, Trump is advised to launch a new round of rhetoric against Big Tech, not over free speech — but over tax patriotism.

One tax policy strategist noted, “Framing this as a fairness issue — ‘Why should small businesses pay full freight while Amazon avoids billions?’ — is potent. It’s populism with a fiscal badge.”

Recovering just half of the currently avoided taxes — say $500 billion over a decade — would meaningfully shrink the deficit. It wouldn’t eliminate the debt crisis, but it could buy time, investor confidence, and political capital.

The Loophole Economy: Bigger Than Any Bailout?

Tax avoidance is no longer about suitcases of cash or shadowy banks. It’s about digital architecture: thousands of shell companies, billions in internal service charges, and subsidiaries in legal limbo. The U.S. Treasury knows this, and in 2022, they tried to fight back. But enforcement is sluggish and tech firms are agile.

One international tax analyst put it this way: “We’re playing checkers. They’re playing recursive 4D chess with their own rulebook.”

Despite the new minimum tax, some companies reportedly still pay less than 3% on billions in profit. When combined with legal interest deductions, cross-border IP flows, and deferred tax credits, the total lost revenue becomes systemic.

And here’s the crucial twist: the U.S. debt crisis is systemic, too.

Trump’s Political Goldmine — Even If It’s Not Fiscal Salvation

Whether or not tax recovery from Big Tech fixes the budget, it fits Trump’s 2025 narrative like a glove:

- It’s visual: a few companies, astronomical numbers, exotic islands.

- It’s emotional: middle America pays taxes while Big Tech “cheats.”

- It’s patriotic: reclaiming profits for “America First.”

- It’s easy to sell: “We lost $60 billion a year to global games. That ends now.”

A former administration economic advisor, now working for a think tank, offered a blunt analysis: “He doesn’t need to fix the debt. He just needs to make it look like someone else broke it — and he’s the only one trying to fix it.”

Already, internal drafts of campaign messaging suggest a pivot toward tech tax enforcement as a major theme in the coming fiscal summit this May. If Trump can frame it as a crusade for fairness — and against elite evasion — it could serve double duty: economic rallying point and political battering ram.

What Comes Next: Real Reform or Rhetoric?

There is appetite for action. Global efforts at tax harmonization, like the OECD’s Pillar Two minimum tax, aim to plug international gaps. But implementation is fragmented. Some U.S. allies resist. Some multinationals adapt faster than regulators.

Table: Overview of the OECD Pillar Two Global Minimum Tax

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Objective | Ensure multinational enterprises (MNEs) pay a minimum effective tax rate of 15% globally. |

| Scope | Applies to MNEs with annual consolidated revenues exceeding €750 million. |

| Key Rules | - Income Inclusion Rule (IIR): Parent companies pay top-up tax for subsidiaries taxed below 15%.- Under-Taxed Profits Rule (UTPR): Imposes additional taxes on payments to low-tax jurisdictions.- Subject-to-Tax Rule (STTR): Taxes specific cross-border payments, focusing on developing countries. |

| Implementation | Countries must adopt rules domestically. Examples include Switzerland (2024) and the EU (2023). |

| Expected Impact | - Generates $150 billion annually in global tax revenues.- Reduces tax avoidance and profit shifting.- Increases compliance burdens for MNEs. |

The fight may shift from tax avoidance to tax invisibility — where no single law is broken, yet no country collects.

But pressure is mounting. If a future IRS campaign — perhaps bolstered by new enforcement tools or whistleblower incentives — begins to crack open complex structures and expose who pays what, the public narrative could tilt hard.

As one senior audit consultant put it, “We are one leaked spreadsheet away from a political wildfire.”

A Trillion-Dollar Mirage or a Strategic Wedge?

Could taxing Big Tech fully solve America’s debt crisis fully? No. But could it provide a trillion-dollar buffer, slow the deficit’s velocity, and deliver a political win framed as economic justice?

Absolutely.

In a moment where fiscal reality and populist instinct collide, President Trump’s focus on corporate tax recovery may not balance the books — but it could balance the narrative. And in 2025, narrative may be the most valuable currency in Washington.