From Textile Ruins to Capital Empire - How Buffett Turned a $7.50 Mistake Into a Financial Juggernaut

From Textile Ruins to Capital Empire: How Buffett Turned a $7.50 Mistake Into a Financial Juggernaut

A Deal Sparked by Ego, Not Logic — And the Billion-Dollar Fallout That Followed

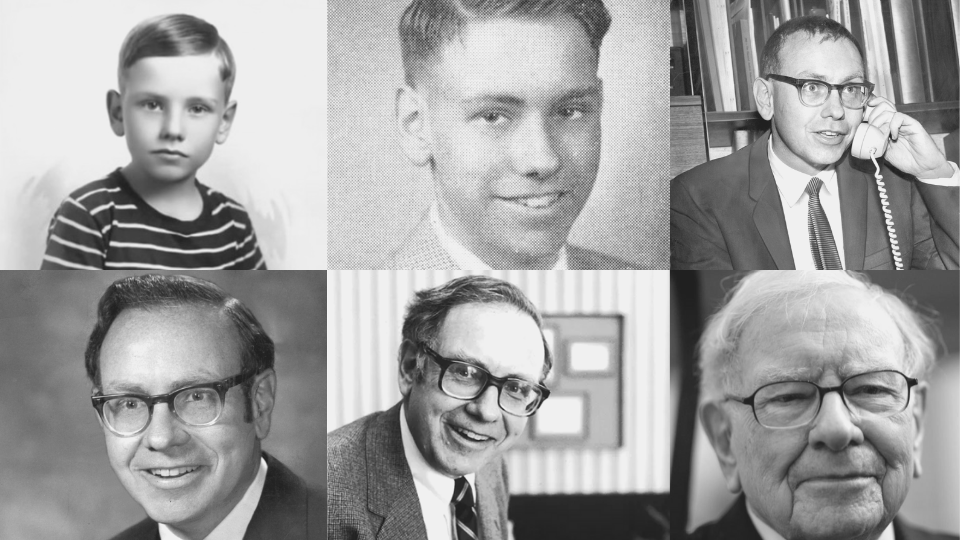

In 1962, a young Warren Buffett spotted what appeared to be a classic value play: Berkshire Hathaway, a faltering New England textile mill trading at $7.50 per share, while its book value hovered around $20. Armed with his Columbia Business School training and a Benjamin Graham lens on deep value, he pounced. But what began as a textbook contrarian bet soon unraveled into one of the most ironically instructive case studies in investment history — one Buffett himself would later call a “monumentally stupid” decision.

What followed, however, was something no textbook could predict: the resurrection of a dying textile shell into the most successful capital allocation engine in modern financial history.

This is not just the story of how Buffett salvaged a bad bet. It is a masterclass in long-term capital strategy, structural arbitrage, and the quiet genius of turning industrial decay into enduring wealth — and it offers rare, hard-earned insights for today’s investors.

Behind the Myth: The Real Story of Buffett’s Berkshire Buy

Buffett began buying shares in Berkshire Hathaway in 1962, lured by its low price relative to book value. The then-CEO, Seabury Stanton, reportedly offered a buyback at $11.50 per share — only to return later with a formal offer of $11.375.

The difference, though mere cents, lit a fuse. Offended by what he saw as a breach of integrity, Buffett doubled down. He began purchasing enough shares to seize control, eventually taking over in 1965.

That decision — driven not by dispassionate logic, but by emotion — locked Buffett into a capital trap. The American textile industry was already crumbling, and New England mills were on the losing end of a brutal cost war against the American South. "It was a dead horse, and I kept feeding it," Buffett would later reflect.

Despite sporadic attempts at operational turnarounds, Berkshire’s textile segment bled capital for two decades. Exact figures on total losses are disputed, but the returns on capital from the textile operations were clearly negative.

How to Turn a Sinking Ship into a Battleship: The Real Buffett Playbook

Beneath the folklore of this fateful acquisition lies a deeper and far more instructive story. Buffett may have stumbled into Berkshire Hathaway, but what he built on its carcass was anything but accidental.

1. The Holding Company as Strategic Weapon

Buffett quickly recognized that while the textile mill was failing, the public shell of Berkshire Hathaway was a valuable corporate structure. He preserved it — not for its operations, but for its legal identity, market listing, and capital markets access.

This move laid the foundation for his empire.

A seasoned analyst who has studied Berkshire’s structural evolution said, “The moment Buffett bought National Indemnity in 1967, the textile business became irrelevant. The holding company became the real asset.”

From there, Berkshire Hathaway transformed into a financial conduit, housing cash-generating businesses like insurance, railroads, and consumer brands. The textile factory kept burning cash — but its corpse was used as scaffolding for a skyscraper.

2. Tax Strategy — But Not the Conspiracy

Much has been speculated — and in some circles, mythologized — about Buffett’s supposed use of “SPVs,” “triangular loss structures,” and “shadow dividend certificates” to minimize tax obligations or regulatory burden. While such claims are rich with imagery, most are unsupported by credible documentation.

What is true — and important — is that Buffett did make strategic use of Berkshire’s textile losses. The tax code allows for Net Operating Losses to offset profits in other business segments. Buffett, using the legal structure of the conglomerate, applied these to new acquisitions, like National Indemnity.

“Nothing exotic,” said a tax attorney familiar with M&A structures. “He used the tax code the way any competent CFO would — the difference is, he did it early, and at massive scale.”

This tax-aware allocation helped preserve capital and amplified compounding returns during Berkshire's early expansion phase.

3. The Insurance Float: Buffett’s Real Leverage

With the acquisition of National Indemnity, Buffett unlocked a powerful source of capital: insurance float. These are premiums collected today for claims that may be paid years later — in effect, interest-free money.

“Most investors look for margin of safety in price. Buffett built margin into structure,” one financial historian noted. “Float allowed him to invest billions before he even earned it. That’s the real alchemy.”

And because Berkshire retained all earnings — famously paying no dividend — Buffett compounded both float and profits internally, tax-deferred.

See’s Candies and the Shift to Quality: A Pivotal Mental Pivot

In 1972, Buffett paid $25 million for See’s Candies, a California-based premium chocolate business that was generating just $4 million in pretax earnings.

To many traditional value investors, the price seemed steep — nearly 7x tangible book. But See’s had something Buffett had previously undervalued: brand power, customer loyalty, and immense pricing leverage.

See’s would go on to produce over $2 billion in cumulative pretax earnings for Berkshire — with minimal need for reinvestment. The lesson? Capital efficiency and economic moats trump raw balance sheet metrics.

“This was the beginning of Buffett’s evolution,” said one investment strategist. “He started chasing return on capital, not just discounts to book.”

Dissecting the Financial Alchemy Myths

A viral narrative recently made waves, claiming that Buffett had engineered a labyrinth of shell companies, sale-leasebacks with “loss betting clauses,” shadow dividends hidden in Swiss bank vaults, and Luxembourg-based capital reserve tricks to boost Tier 1 ratios.

While the story was told with cinematic flair, it largely collapses under scrutiny.

“There’s zero evidence Buffett engaged in offshore dividend recharacterizations or hidden SPVs for See’s Candies,” said a former SEC accountant. “The real brilliance was much simpler — he owned quality businesses outright and let the cash compound.”

Berkshire’s financials, subject to stringent U.S. GAAP and public disclosures, have been lauded for their transparency and integrity. If anything, Buffett’s reluctance to engage in financial engineering — not his embrace of it — is a defining hallmark of his success.

Lessons from the Noise: What Investors Can Actually Learn

Beneath the embellished stories and exaggerated finance cosplay lies a wealth of actionable insight for serious investors:

1. Structural Arbitrage > Tactical Trading

Buffett’s genius wasn’t in day-trading stocks — it was in understanding how legal entities, tax laws, and capital flows could be organized for compounding. “Think like an architect, not just a stock picker,” said one private equity manager.

2. Capital Allocation is Destiny

Buffett failed to fix the textile business — but he succeeded by refusing to let its failure trap future capital. He redeployed every dollar into businesses with better returns, a lesson today’s conglomerates often ignore.

3. Emotional Discipline Trumps IQ

The Berkshire takeover began as an emotional overreaction — a rare lapse from the Oracle. But it became a case study in how to rescue a mistake through relentless adaptation.

4. Time is the Real Leverage

Unlike financial leverage, which amplifies both gains and losses, time — when paired with compounding and prudent capital allocation — creates asymmetric returns. Buffett’s strategy wasn’t get-rich-quick; it was get-rich-forever.

A Mistake That Made Trillions

Buffett calls the Berkshire Hathaway purchase his worst trade — a mistake that cost him billions had he invested instead in insurance companies or Coca-Cola directly. But that same “mistake” became the shell through which he assembled the greatest conglomerate of the modern era.

In many ways, Buffett didn’t just turn lemons into lemonade. He built a cash fountain from the rind.

The lesson isn’t that mistakes don’t matter — it’s that the real test of an investor is what they do next. Buffett built an empire not by avoiding failure, but by transforming it into fuel.

As one portfolio manager put it, “He turned a rusting factory floor into the Vatican of capital allocation. That’s not luck. That’s a different species of thinking.”

And for investors today, there’s no better homework worth copying.