As TSMC Dominates, Japan Bets Billions on a Radical Chip Gamble - Inside Rapidus’s High-Stakes Bid to Rewire the Semiconductor World

As TSMC Dominates, Japan Bets Billions on a Radical Chip Gamble: Inside Rapidus’s High-Stakes Bid to Rewire the Semiconductor World

On the wind-swept plains of Chitose, in northern Japan’s Hokkaido prefecture, a silent revolution is beginning to hum. Inside a sleek industrial facility encased in reflective steel and glass, a prototype production line is gearing up to attempt what some in the semiconductor world consider bordering on the impossible: to challenge Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s (TSMC) global dominance in cutting-edge chips, and do it on a faster clock, with a leaner model, from scratch.

The company behind the move is Rapidus, a little-known startup outside Japan until recently. But its ambitions, fueled by billions in public and private capital, are anything but modest. By 2027, Rapidus aims to mass-produce 2-nanometer chips—advanced silicon components that power everything from smartphones to artificial intelligence (AI) systems—putting it in direct contention with TSMC and Samsung, the undisputed titans of the $90 billion global foundry market.

“Growing tensions between the U.S. and China have raised voices about requiring another vendor for chips,” noted Rapidus CEO Atsuyoshi Koike, framing the company’s strategy not just as technological ambition, but as geopolitical hedging.

Global semiconductor foundry market share by revenue, highlighting TSMC's dominance.

| Foundry | Market Share (%) | Quarter/Year |

|---|---|---|

| TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.) | 67.1% | Q4 2024 |

| Samsung Electronics | 8.1% | Q4 2024 |

| SMIC (Semiconductor Manufacturing Int'l Corp.) | 5.5% | Q4 2024 |

| UMC (United Microelectronics Corp.) | 4.7% | Q4 2024 |

| GlobalFoundries | 4.6% | Q4 2024 |

| HuaHong Group | 2.6% | Q4 2024 |

And now, as revealed by Nikkei business daily today, the company is deep in negotiations with some of the biggest names in tech: Apple, Google, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft. These aren’t deals yet—but they signal a tectonic undercurrent: the semiconductor world may be preparing for a realignment.

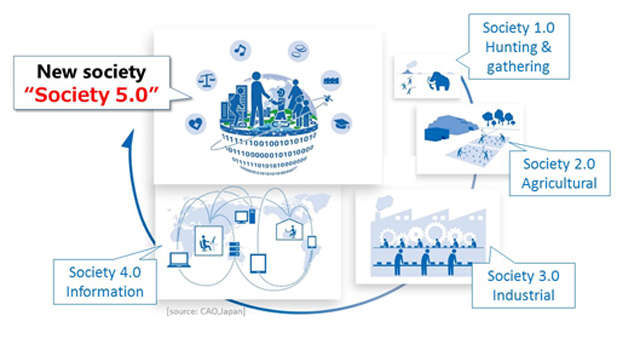

The Strategic Pivot: Japan’s Industrial Gamble

For decades, Japan was a semiconductor heavyweight. Names like Toshiba and NEC once dominated global memory chip markets. But as the era of logic chips and foundries dawned, Japan was outmaneuvered. TSMC, with its scale and precision, became indispensable. Today, over 90% of the world’s most advanced chips are manufactured in Taiwan—an uncomfortable concentration given rising U.S.-China tensions and growing concerns over Taiwan’s geopolitical exposure.

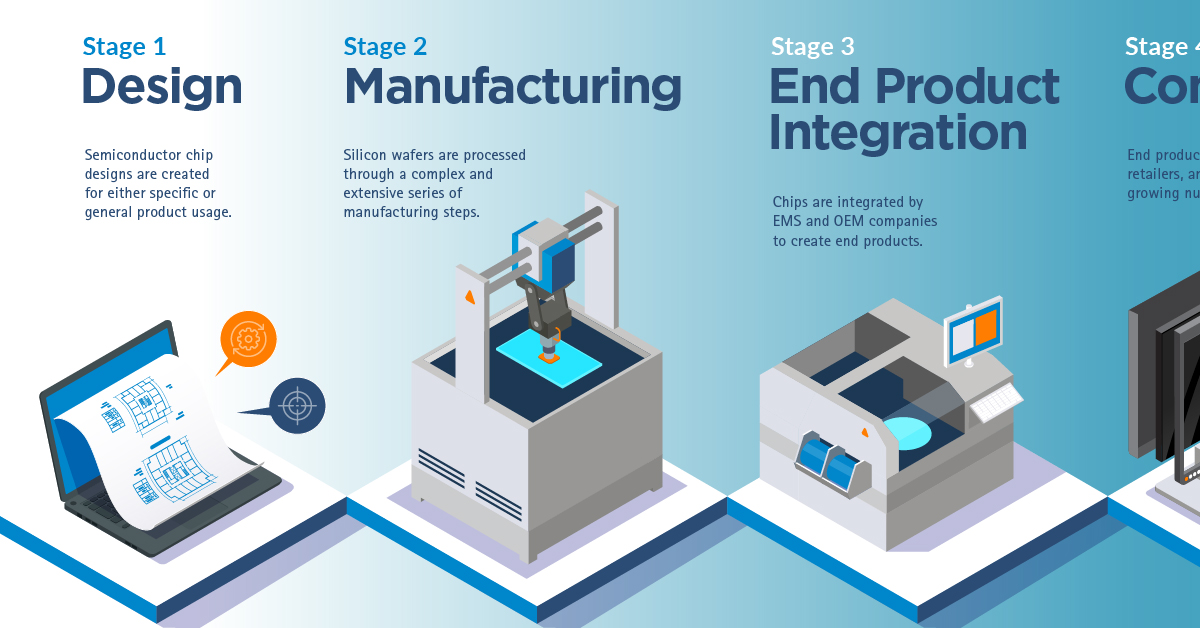

The semiconductor foundry model involves companies specializing solely in manufacturing integrated circuits based on designs provided by other companies, often called fabless semiconductor firms. Unlike Integrated Device Manufacturers (IDMs) who design and produce their own chips, foundries operate as contract manufacturers, focusing purely on the fabrication process for their clients.

“Growing tensions between the U.S. and China have raised voices about requiring another vendor for chips,” said Rapidus CEO Atsuyoshi Koike, framing the venture as both a business move and a geopolitical imperative.

To that end, Tokyo is going all-in. Starting this fiscal year, the Japanese government will inject ¥200 billion (approximately $1.37 billion) into Rapidus, with more funds expected under its national semiconductor strategy. Eight major Japanese firms—including Sony, Toyota, and SoftBank—have also thrown their weight behind the venture, signaling a rare alignment of political will and industrial muscle.

Rapidus’s Big Bet: Jumping the Gap with 2-nm Ambitions

The technical bar couldn’t be higher. TSMC is already producing 2-nm chips this year. Intel and Samsung are racing down the same path. Rapidus, meanwhile, is just now lighting up its prototype line. The timeline is audacious: three years to go from a partially operational pilot plant to full-scale, commercial-grade mass production of one of the most advanced technologies on Earth.

The 'nanometer' measurement (e.g., 2nm) in chips refers to a specific generation or "node" of semiconductor manufacturing technology. While historically related to the size of features like transistors, it now primarily serves as an industry label indicating increased transistor density, leading to improved performance and energy efficiency compared to older nodes.

Unlike its rivals, however, Rapidus isn’t trying to scale the same mountain. Instead, it’s carving a different path, aiming to outmaneuver, not outmuscle. The company plans to leapfrog legacy manufacturing models with a single-wafer processing approach—a potentially faster feedback loop that allows real-time quality control and customization.

This model might appeal to AI-focused customers needing quick iteration and specialized chip designs. But it’s also unproven at scale.

“The traditional model is built for volume. Rapidus is betting on speed and specificity,” said one Tokyo-based chip industry analyst who requested anonymity. “That’s clever, but if your yields don’t rise fast enough, your cost base kills you.”

Can It Scale? The Yield Curve and Manufacturing Gauntlet

At the heart of any chip foundry lies a brutal equation: yield. How many functional chips can you extract per wafer? TSMC’s edge comes not just from engineering prowess but from a decade-long obsession with incremental yield gains that drive down cost per unit. Rapidus, by contrast, is targeting a first-run yield of 50%, aiming for 80–90% over time—a stretch goal that some experts call “mathematically optimistic.”

In semiconductor manufacturing, yield refers to the percentage of functional chips, or dies, successfully produced from a silicon wafer relative to the maximum possible number. It's a critical metric because higher yields indicate greater manufacturing efficiency and directly translate to lower production costs per chip. Illustrative semiconductor manufacturing yield improvement curve over time for a new process node.

| Phase | Typical Timeframe | Yield Range (Illustrative) | Key Factors & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| R&D / Pilot | Initial phase | Low (< 50%) | Process stabilization, identifying major defect sources, testing initial designs. Yield is highly variable and often constrained by systematic issues. |

| Ramp-Up | First few quarters of production | 50% - 80% | Volume production begins. Focus shifts to rapid yield learning, defect reduction, process optimization, and identifying systematic vs. random defects. |

| Maturity | 1-3 years post-introduction | > 80% - 90%+ | Process is stable, yield improvements slow down (approaching entitlement yield). Focus on cost reduction, minor process tweaks, and maintaining stability. |

| Refinement | Ongoing through node lifecycle | > 90% | Continuous improvement, cost optimization through process adjustments (e.g., reducing EUV layers), potentially introducing enhanced versions of the node (e.g., N3 -> N3E). |

The risks of this approach are high. Any stumble in early yield could send costs soaring and clients running back to safer shores.

“There’s zero room for delay,” said a U.S.-based semiconductor consultant familiar with Rapidus’s process flow. “Every quarter missed is not just money burned—it's trust lost.”

Adding to the challenge, Rapidus is building its ecosystem from scratch. Unlike TSMC, which sits at the nexus of a mature supply chain in Taiwan, Rapidus must coordinate equipment, tooling, photomask infrastructure, packaging, and testing across a country that hasn't built leading-edge chips in decades.

To bridge this gap, the company has partnered with IBM for core technology transfer. But execution remains everything.

Negotiations vs. Orders: The Chasm Between Interest and Commitment

The Nikkei report that Rapidus is in talks with Apple, Google, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft has lit up investor circles. But so far, these are exploratory negotiations—not contracts. The distinction is critical.

Major tech firms are increasingly diversifying their supplier base. The U.S. CHIPS Act has nudged them toward domestic or allied production, and Japan is an attractive destination given its engineering base and political alignment. But no major customer has yet signed a binding agreement with Rapidus.

“It’s a hedge,” said one supply-chain strategist at a U.S. cloud company. “They’re taking meetings, running the numbers. But nobody’s going to commit until there’s a fab pushing consistent wafers with reliable yields.”

Indeed, the lesson from GlobalFoundries—a U.S.-based foundry that attempted to go toe-to-toe with TSMC and ultimately retreated from the bleeding edge—is that ambition alone isn’t enough. Scale, ecosystem, and time all matter.

The Government Factor: Public Capital Meets Private Risk

Rapidus’s single biggest backer is the Japanese state. That’s both a strength and a risk.

Politically, it signals that the project is of national importance—akin to Japan’s space program or high-speed rail investments. Economically, it de-risks early losses. But it also raises the stakes. A failure could be read not just as a corporate misstep but as an indictment of state-led industrial policy.

“There’s a very real possibility Rapidus becomes a symbol,” said a former Japanese trade official. “Either of national resurgence—or of the dangers of industrial nostalgia.”

Still, the broader economic potential is enticing. If Rapidus succeeds, it could catalyze an entire value chain—boosting employment in high-tech sectors, attracting EDA and equipment firms back to Japan, and reducing reliance on Korean and Taiwanese imports.

The Battle for the Future: Strategic Implications for the Global Chip War

The semiconductor world is in flux. AI is reshaping compute needs. Geopolitical tensions are redrawing supply maps. Climate risk, labor shortages, and rising fab costs are all chipping away at the old foundry model. Projected growth of the global AI chip market revenue.

| Forecast Period | Projected Market Value | CAGR | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 - 2029 | USD 311.58 billion by 2029 | 20.4% | MarketsandMarkets |

| 2023 - 2032 | USD 383.7 billion by 2032 | 38.2% | Allied Market Research |

| 2024 - 2032 | USD 174.48 billion by 2032 | 15.2% | SNS Insider |

| 2024 - 2033 | USD 501.97 billion by 2033 | 35.50% | Astute Analytica |

| 2024 - 2034 | USD 232.85 billion by 2034 | 15.23% | Precedence Research |

| 2024 - 2035 | USD 846.85 billion by 2035 | 34.84% | Roots Analysis |

| By 2030 | Nearly USD 1 trillion | N/A | PwC (via Anadolu Agency) |

Against this backdrop, Rapidus’s proposition—agile, customizable, sovereignty-friendly chip manufacturing—isn’t just plausible. It’s timely.

If the company can hit its 2027 targets, even modest market share—5 to 10% of high-performance foundry demand—could force incumbents to pivot. TSMC might need to accelerate capacity in Japan or the U.S. Samsung may reconsider its contract manufacturing pricing. Nvidia, AMD, and even start-ups might have new options to prototype AI accelerators at speed.

But the opposite is equally true: should Rapidus falter, the venture could become a case study in how not to build a foundry from the ground up.

A Razor's Edge Between Reinvention and Overreach

Rapidus is trying to do something no one has done in a generation: build a national champion in advanced semiconductors—fast, from scratch, and against the clock. It has money, talent, and a geopolitical tailwind. It also faces a gauntlet of manufacturing, economic, and execution risk.

For investors and strategists, the question is no longer whether Rapidus matters. It’s whether it can deliver. The next two years—across yield targets, customer signings, and ecosystem buildout—will determine whether this becomes Japan’s semiconductor renaissance or just another footnote in the long saga of tech disruption.

Until then, the machines in Hokkaido are warming up. And so is the race.