Shenzhen Launches House Voucher System, Joining Beijing Shanghai and Guangzhou in Overhauling Urban Renewal Compensation

In China’s Mega-Cities, a Radical Housing Voucher Experiment Is Underway

Shenzhen Joins Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou in Rolling Out the “Fang Piao (Housing Voucher)” — a Quasi-Currency Aimed at Real Estate Recovery, Urban Renewal, and Fiscal Survival

SHENZHEN — In a move laden with symbolic and systemic weight, China’s four first-tier cities—Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and now Shenzhen—have formally launched the experimental "Fang Piao System" or "house ticket system," a voucher-based approach to urban renewal compensation that may herald a paradigm shift in how China finances its housing ambitions.

On March 26, Shenzhen’s Housing and Urban-Rural Development Bureau issued a landmark directive: starting April 9, the city will replace—or at least significantly complement—cash compensation for urban renewal projects with house tickets. These vouchers can be exchanged for designated residential units, often with additional bonuses like extra square footage. Supporters see the move as a pragmatic attempt to resolve multiple crises at once. Critics argue it’s a clever repackaging of old debt and inequality in shiny new wrappers.

But make no mistake: this is no bureaucratic footnote. The house ticket system is China’s latest attempt to steer its real estate sector—a pillar of the nation’s economy—back from the brink, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

A New Currency for the Urban Battlefield

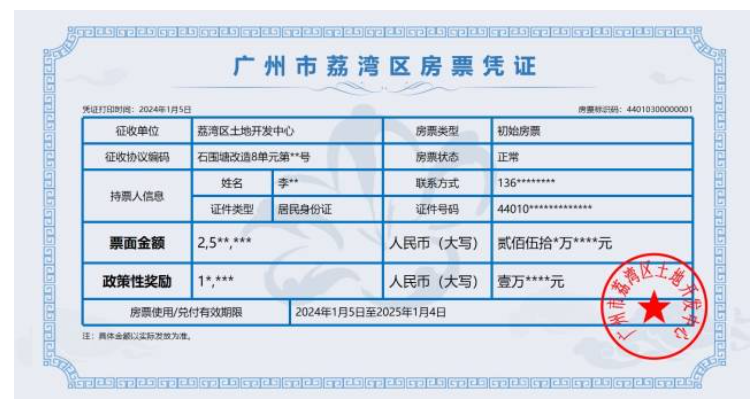

In principle, the house ticket is simple: rather than handing displaced residents a cash payout, local governments issue them a voucher—valid for about a year—that can be used to purchase newly built, government-approved housing. Often, these tickets include incentives like 10–20% bonus area, or fast-track access to modern apartment complexes that are already built, sidestepping the delays and risks of waiting for new construction.

But the mechanism is far from neutral. "It looks like a housing voucher, but behaves like a municipal bond with a residential address," observed one policy analyst familiar with Guangdong's fiscal architecture. "It’s not just about housing—it’s about liquidity, political trust, and local solvency."

Indeed, the house ticket operates in a delicate dance between three forces: developers holding unsold inventory, governments facing mounting fiscal constraints, and residents increasingly skeptical about the promises of urban redevelopment.

From Blueprint to Battlefield: How the Policy Took Root

Shenzhen’s adoption follows a cascade of earlier experiments. Guangzhou led the way in early 2024 with its “Housing Voucher Implementation Plan,” making it the first of the four to operationalize the idea. Beijing’s Tongzhou district followed with a draft in July, while Shanghai began its implementation in Jinshan and Qingpu districts.

The context is both urgent and structural. As part of a national push for urban village transformation—especially following the 2023 Economic Work Conference which set a goal of 100 million square meters of redevelopment—local governments found themselves facing a classic trilemma: no money to compensate, no time to wait, and no political appetite for mass protests. China's Real Estate Investment Growth Year-on-Year, showing recent slowdown trends.

| Metric | Period | Value/Change (YoY) |

|---|---|---|

| Real Estate Investment | Full Year 2024 | -10.6% |

| Real Estate Investment | Jan-Feb 2025 | -9.8% |

| Commercial Building Sales (Floor Area) | Full Year 2024 | -12.9% |

| Commercial Building Sales (Value) | Full Year 2024 | -17.1% |

| New Home Sales Value (Top 100 Developers) | Feb 2025 | +1.2% |

| New Construction Starts (Floor Area) | Full Year 2024 | -23.0% |

| New Home Prices (70 Cities) | Feb 2025 | -4.8% |

| Residential Buildings Completed (Floor Area) | Full Year 2024 | -27.4% |

| Floor Space of Commercial Buildings for Sale | End of 2024 | +10.6% |

“The traditional model of building relocation housing was too slow and too expensive,” noted one urban redevelopment consultant. “But just handing out cash? Also unaffordable. Fang Piao is the compromise.”

Shenzhen’s announcement codifies the policy shift that has been years in the making. The city explicitly tied the new mechanism to broader urban renewal goals, including the revitalization of stock housing, support for real estate developers, and municipal debt control.

Incentives and Illusions: What the House Ticket Actually Does

Liquidity Without Cash

The house ticket is, functionally, a localized credit instrument. It doesn’t come with interest, isn’t universally accepted, and has an expiration date. But it does unlock purchasing power within a narrow band of properties.

“This is quasi-money,” said one macroeconomist. “It’s a shadow financial instrument without the full backing of central monetary authority—but strong enough to redirect economic activity within specific urban zones.”

Quasi-currency, also termed quasi-money, refers to highly liquid assets like scrip that function similarly to official money but aren't legal tender. These instruments are easily convertible or usable within specific contexts, yet lack the universal acceptance of government-issued currency.

By directing this purchasing power toward designated housing stock, cities aim to clear out bloated developer inventories while offering displaced residents what officials describe as a “more dignified, more flexible” housing solution. In Shenzhen’s case, this might mean channeling demand toward less saturated districts like Longgang or Pingshan.

Developers Find a Lifeline

For developers—especially those still reeling from regulatory clampdowns and a liquidity crunch—the house ticket system offers something they’ve craved: captive demand.

“Fang Piao is demand with no escape route,” one Guangdong-based property executive said. “Residents can’t hold onto the cash, can’t invest it elsewhere, can’t just leave the market. They have to buy.”

But this comes with strings attached. Developers must negotiate discounts, absorb uncertain timing in voucher redemption, and coordinate with local governments on compliance. In many cases, vouchers can only be used on a short list of approved projects, often dictated by local political and fiscal priorities.

In Guangzhou’s Liwan district, for instance, one voucher worth 2.5 million yuan effectively only granted access to a narrow range of options—many above that price point, requiring displaced residents to top up with their own cash.

Displaced but Disempowered? Residents Face Tough Choices

From the standpoint of urban dwellers in the path of bulldozers, the shift from cash to voucher brings both promise and peril.

On one hand, the house ticket may enable access to modern housing that otherwise would be unaffordable.

On the other, the constraints are real: limited selection, expiration risk, no investment utility, and little flexibility.

“You can’t put a Fang Piao in your bank account. You can’t invest it. You can’t pass it on to your kids,” noted one commentator. “And if the available properties are overpriced or subpar, you’ve effectively just lost purchasing power.”

Some local rules even require residents to use at least 90% of the voucher’s value, as seen in cities like Shenyang. If the full amount isn’t used, it’s forfeited. In extreme cases, residents can’t opt out of the system—even if they prefer to wait for cash compensation.

Shadow Finance, Silent Tradeoffs: The Fiscal Mechanics Behind the Curtain

Beneath the social and political theater lies a complex monetary structure that makes Fang Piao far more than a simple housing policy. It’s part of a broader recalibration of how capital flows through China's most critical sector: real estate.

The Three-Layered Money Machine

Analysts break the traditional property finance cycle into three core layers:

- Policy Bank Lending: Local governments borrow from policy banks to fund monetary compensation—a process that prints new money and creates public debt. I'll reformat this data into a cleaner table by removing the sources and reorganizing the information properly:

Table: Growth of China's Local Government and LGFV Debt (2014–2023)

| Year | Metric | Value (Trillion RMB) | Value (% of GDP) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | LGFV Debt | ~14.34 | ~13% | IMF estimates LGFV debt at 13% of GDP. Debt swap program initiated. |

| 2020 | LGFV Debt | ~45 | ~44% / ~88% | IMF estimated risky LGFV debt at 20.1 Trillion RMB (44% of total). Li estimated total local debt at 90 Trillion RMB (~88% of GDP). |

| End 2022 | LGFV Debt | 59-60+ | ~47-50% | Rhodium Group: 59 Trillion RMB. IMF: 60+ Trillion RMB. UCSD estimates total local debt (bonds + loans) at 90-110 Trillion RMB (~75-91% of GDP). |

| End 2023 | Official Local Government Debt (on-balance) | ~41 | ~32% | Official figures reported. |

| End 2023 | LGFV Debt (off-balance / hidden) | ~60 | ~48% / ~60% | IMF estimates LGFV debt at 60 Trillion RMB (~48% of GDP). AXA IM estimates total local debt (incl. LGFVs) at ~76 Trillion RMB (>60% of GDP). |

| End 2023 | General Government Debt (Official) | ~71 | ~69% / ~83.4% | Includes central + local government debt. IMF reports higher ratios. |

| End 2023 | Augmented Government Debt (Official+LGFV) | ~101 | ~117% / ~120% | IMF's "augmented" ratio includes LGFV estimates. |

Did you know that China has a unique set of state-owned financial institutions known as policy banks? These banks, including the China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank of China, and Agricultural Development Bank of China, are designed to implement government economic policies rather than maximize profits. They specialize in targeted financing for sectors like infrastructure, trade, and agriculture, and play a crucial role in supporting China's strategic initiatives, both domestically and internationally. Policy banks are instrumental in funding projects under the Belt and Road Initiative and are a key tool for China to advance its economic goals globally. Despite lacking explicit government guarantees, their bonds are considered sovereign due to their critical role in China's development strategy.

- Developer Financing: Real estate firms take out loans, buy land from governments, who then repay debt and fund infrastructure. This fuels both public and private leverage.

- Household Borrowing: Citizens take out mortgages to buy homes, completing the chain of debt-fed growth. The result is an economy where real estate has functioned not as a reservoir but an “infinite money printer.”

The house ticket disrupts this sequence. It reduces upfront liquidity needs from the government, lowers financing costs (no interest), and allows for localized monetary expansion without hitting formal debt ceilings. In short, it’s an IOU with zoning laws.

But the system’s credibility hinges on the value residents place on these IOUs. If the ticket is perceived as weak—due to poor housing options or weak developer trust—it could spark resistance.

Risks: Quiet Crisis or Subtle Stabilizer?

The house ticket’s effectiveness depends on four unpredictable variables:

- Creditworthiness of Local Governments: Especially in lower-tier cities, residents may question whether vouchers will retain value or be honored fairly.

- Developer Execution Risk: If projects are delayed or halted, the voucher becomes worthless, and resident trust erodes rapidly.

- Resident Preferences: People displaced from urban villages often desire mobility, not mandatory reinvestment into static assets.

- Market Segmentation: Over time, two property markets may emerge—voucher-eligible and ineligible—leading to distortion, illiquidity, and equity concerns.

Some analysts warn of an even deeper risk: the creation of localized, unregulated quasi-currencies that blur the line between fiscal management and shadow finance. “This isn’t just policy innovation. It’s monetary improvisation,” one expert said. “And the long-term effects are unknown.”

What Comes Next: Expansion, Evolution, or Exhaustion?

The model is now expected to extend beyond urban village demolition into other domains: shantytown redevelopment, public housing conversion, and even buy-first-sell-later schemes, where governments might acquire resident-owned homes in exchange for—what else—more Fang Piao.

But skepticism lingers.

As one lawyer specializing in urban expropriation put it: “A voucher is fine—if the market works. But what happens when the music stops, and everyone’s holding a piece of paper no one wants?”

A Policy Built on Promise and Fragility

China’s house ticket experiment is a striking blend of fiscal triage, real estate stimulus, and social engineering. It seeks to patch together a fraying policy consensus with an instrument that is equal parts subsidy, IOU, and market mechanism.

If successful, it may help stabilize the country’s most volatile economic sector and modernize its approach to urban renewal. If it falters, it could expose the limits of financial creativity in the face of structural imbalance.

For now, developers cheer, officials breathe a little easier, and displaced residents weigh their odds.

As one anonymous analyst put it, “Fang Piao is not about real estate. It’s about trust. Trust in the system, in the city, in the future. And that’s the hardest currency of all.”